The Weird History and Chemistry of Prussian Blue

Introduction

Prussian Blue, with its deep and captivating hue, holds a significant place in the realm of pigments, blending a fascinatingly dark history with chemical ingenuity. Originally discovered in the 18th century by the Swiss chemist Johann Jacob Diesbach, Prussian Blue emerged as a groundbreaking innovation, bridging the worlds of science and art.

This exploration will delve into the pigment properties, history, chemical properties, and modern applications of Prussian Blue, tracing its evolution from the laboratory to the canvas and beyond.

Pigment Properties and Examples

Artists swiftly embraced Prussian Blue for its intense color saturation, remarkable lightfastness (resistance to fading), and ability to create a wide range of tones and effects in painting, printmaking, and textile dyeing. Its versatility allowed artists to achieve both transparent glazes and opaque layers, making it a favored pigment among masters of various artistic movements.

As shown above, the famous and recognizable Katsushika Hokusai woodblock print titled The Great Wave or Under the Wave off Kanagawa from the series Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji. The deep, vivid blues of the towering waves use imported Prussian blue.

Prussian Blue's ability to evoke a wide range of emotions and atmospheres has made it a staple in the artistic palette, serving as a vehicle for creative expression and visual storytelling across diverse cultures and time periods.

History of Use and Trade

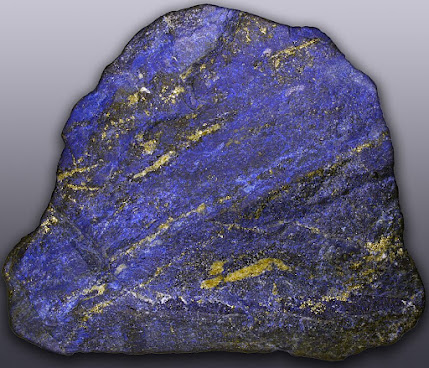

Prussian Blue's popularity soared across Europe and beyond, becoming a staple pigment in the 18th and 19th centuries and shaping artistic palettes worldwide. What made it especially popular was that it was the first lightfast pigment since the loss of Egyptian blue. Blue is very hard to come by in nature, and what little there is usually fades faster than other colors. It was also significantly cheaper than the competition as the other popular blue, ultramarine, was made form lapis lazuli. Lapis lazuli is only mined in Afghanistan, making it rare and costly.

As time went on there was more experimentation done with the pigment itself. Its utility extended beyond the realm of art, finding applications in currency printing, blueprinting, and even medicinal treatments, underscoring its significance in international trade and commerce.

The widespread availability and use of Prussian Blue fostered cultural exchange, enriching artistic practices and visual vocabularies across diverse regions and societies. Its deep, resonant hue became synonymous with qualities such as stability, authority, and even melancholy, shaping perceptions and interpretations in art, literature, and culture.

Origins and Chemistry

Prussian Blue owes its discovery to the serendipitous experiments of Johann Jacob Diesbach, who stumbled upon its rich pigment while at work making dye. He was trying to create a standard red carmine dye. The process to make the dye usually consists of potash, ferric sulphate Fe2(SO4)3, and dried cochineal. What are these substances? Potash is the term for extracted potassium salts that are water soluble. It is called potash because the original method of production was to collect wood ash, leach the potassium salts in water, and boil off the water leaving a white, powdery substance. Potassiums actually got its name from potash. Ferric sulphate is a mordant or a chemical used to make dyes permanent by helping the color bond to different materials. Cochineal are insects that contain carminic acid and used to make carmine dye. Combining the three should usually result in red carmine dye, as mentioned. However, Diesbach was in a rush as he was behind on orders and used potash mixed with human blood. This introduced more iron into the mix, and resulted in a blue pigment. Diesbach inadvertently created a pigment that would revolutionize the world of art and have terrible consequences in other fields.

Formula: (Fe4[Fe(CN)6]3) or Fe7(CN)18

Chemically known as ferric ferrocyanide, Prussian Blue's distinctive hue emerges from its unique molecular structure, formed through the intricate bonding of iron, carbon, and nitrogen ions. This molecular complexity contributes to its remarkable stability and lightfastness, qualities that have ensured its enduring popularity among artists. Unfortunately, the cyanide in ferrocyanide can be easily reacted out and into the acid, hydrogen cyanide, or Prussic acid. This acid was processed into multiple products and chemicals, namely Zyklon. Zyklon A was used as a pesticide until it was used against the French by Germans in World War I. Zyklon A was then banned, leading to a chemically similar product called Zyklon B. Also used as a pesticide until the Germans used it in a concentration camp in the gas chambers.

Situating Prussian Blue within its historical context reveals not only its chemical complexity but also its pivotal role in advancing the science of chemistry during the Age of Enlightenment (around the 17th and 18th centuries). Its discovery sparked a wave of experimentation and innovation, laying the groundwork for future discoveries in the field of synthetic chemistry. It also has a dark history as part of the worst wars in human history.

Modern Applications

Prussian Blue's legacy lives on in modern times through innovative techniques and interdisciplinary collaborations. It has the ability to sequester monovalent metallic cations. Monovalent means that it only has the ability/valency to form one bond. A cation is a positive ion rather than an anion or negative ion. This means that Prussian blue has use in medicine as a way top get rid of toxic heavy metals in the body. The main metals that it is used for are Thallium and radioactive isotopes of Cesium (alternatively spelled Caesium).

As Prussian Blue continues to evolve and adapt in response to contemporary challenges and opportunities, its enduring relevance underscores the dynamic interplay between art, science, and culture. By embracing innovation and collaboration, we can unlock new possibilities for Prussian Blue and other traditional pigments, ensuring their continued vitality and relevance in a rapidly changing world.

Moving forward, let us celebrate the timeless allure of Prussian Blue and its contributions to our shared cultural heritage, fostering a deeper appreciation for the intricate interplay between color, chemistry, and creativity. Through ongoing research and creative experimentation, we can honor Prussian Blue's legacy and ensure that its vibrant hue continues to inspire future generations of artists, scientists, and enthusiasts alike.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment