The Weird History and Chemistry of Verdigris Green

Introduction:

In the realm of pigments, few colors possess the mystique and allure of verdigris green. This pigment has fascinated artists, scientists, and historians for centuries. Join us on a journey as we explore the origins, properties, artistic applications, and uses of verdigris green, uncovering the beauty, complexity, and danger hidden within its verdant hues.

Origins and Formation:

Verdigris green originates from the gradual oxidation and weathering of copper, resulting in the formation of copper(II) acetate and/or copper carbonate. Historical literature and sources are not clear on what exactly verdigris is/was. Various copper salts have been called verdigris. But, we'll dive more into that in the chemistry section.

Natural processes such as exposure to air, moisture, and acidic environments contribute to the transformation of copper surfaces into the characteristic green patina known as verdigris. it can be observed on the Statue of Liberty, as shown at the top of this blog post.

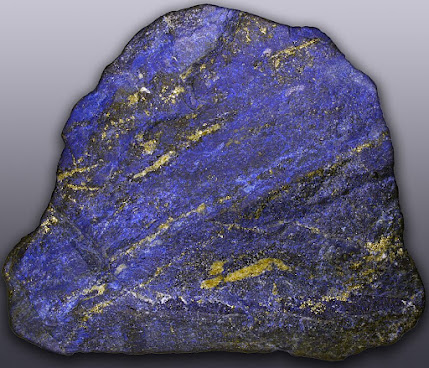

There are many natural varieties of verdigris. Malachite, hoganite, spertiniite, tribasic copper chloride. All of these will be shown below in order.

Ancient civilizations, including the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans, harnessed the transformative power of verdigris for artistic and architectural purposes, recognizing its aesthetic appeal as one of the purest greens available.

Chemical Composition and Properties:

Verdigris green's chemical composition primarily consists of copper compounds, including copper acetate Cu(CH3COO)2, basic copper carbonate Cu2(OH)2CO3, tribasic copper chloride Cu2(OH)3Cl, and copper hydroxide Cu(OH)2.

The vibrant green coloration of verdigris arises from the interaction of copper ions with atmospheric oxygen and carbon dioxide, resulting in the formation of various copper complexes.

Despite its striking appearance, verdigris possesses corrosive properties and can be harmful to artworks and metal artifacts if not properly stabilized and maintained.

Artistic Applications:

Throughout history, verdigris green has been prized as a pigment in painting, sculpture, and decorative arts for its vivid color and unique texture.

Renaissance artists, such as Leonardo da Vinci and Jan van Eyck, utilized verdigris green in their paintings to depict landscapes, drapery, and architectural details with remarkable realism and depth.

Below is a painting titled Christ Crowned with Thorns created by Hieronymus Bosch in 1510. The robe of the man in the upper-left is painted primarily with verdigris green with lead-tin yellow to highlight. below the Bosch painting is Jan van Eyck's The Arnolfini Portrait from 1434. The woman's dress is very green and was painted using verdigris.

Conservation and Ethical Considerations:

Preserving artworks containing verdigris green presents unique challenges due to its susceptibility to degradation and color change over time, like many older pigments.

Conservation efforts focus on stabilizing verdigris patinas, preventing further corrosion, and protecting artworks from environmental factors such as humidity, pollution, and temperature fluctuations.

Conclusion:

Verdigris green stands as a testament to the transformative power of nature and the enduring appeal of pigments derived from the earth. As we marvel at its verdant beauty and contemplate its cultural significance, let us embrace responsible stewardship and ethical engagement with verdigris, ensuring that its timeless legacy continues to inspire and captivate future generations.

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment